Extremely rare planets among the first discovered

They revolve around pulsars and have been detected since the early 1990s. However, they turn out to be exceptional as this type of stars is particularly rare. Moreover, scientists still do not understand how they could have been formed nor how they could resist the cataclysmic conditions that prevail in these systems.

In 1995, the world discovered 51 Pegasi b, the very first exoplanet orbiting a Sun-like star discovered by the Swiss astrophysicists Michel Mayor and Didier Queloz, thanks to observations carried out at the Haute-Provence Observatory using the radial velocity method. Since then, more than 4,000 other stars have joined the bestiary of these extrasolar planets. Some are similar to the Earth, others are gas giants rotating very close to their stars and there could even be bodies composed entirely of diamonds! A great diversity, but the rarest planets are perhaps to be found around objects other than typical stars: pulsars.

First planets detected

In fact, even before the publication of 51 Pegasi b in the journal Nature on November 1, 1995, other planets had already been discovered at the beginning of 1992 thanks to observations made with the Arecibo telescope. But as they did not revolve around a "classical" star and their observation was still subject to various interpretations, the scientific community had not considered them as perfectly conclusive. Since then, their existence has been confirmed: there would be at least three of similar mass to the rocky planets of the solar system and orbiting a pulsar named PSR B1257+12. And their detection is undoubtedly a very big stroke of luck, as planets around this type of star are rare.

This is at least what it appears following a vast survey conducted by astronomers from the University of Manchester whose results were announced at the National Astronomy Meeting held at the University of Warwick (England) from July 11 to 15, 2022. The astronomers have collected observations made at the Jodrell Bank Observatory in northwest England on 800 pulsars over the past 50 years. The verdict: less than 0.5% of all known pulsars could host Earth-mass planets.

A violent environment

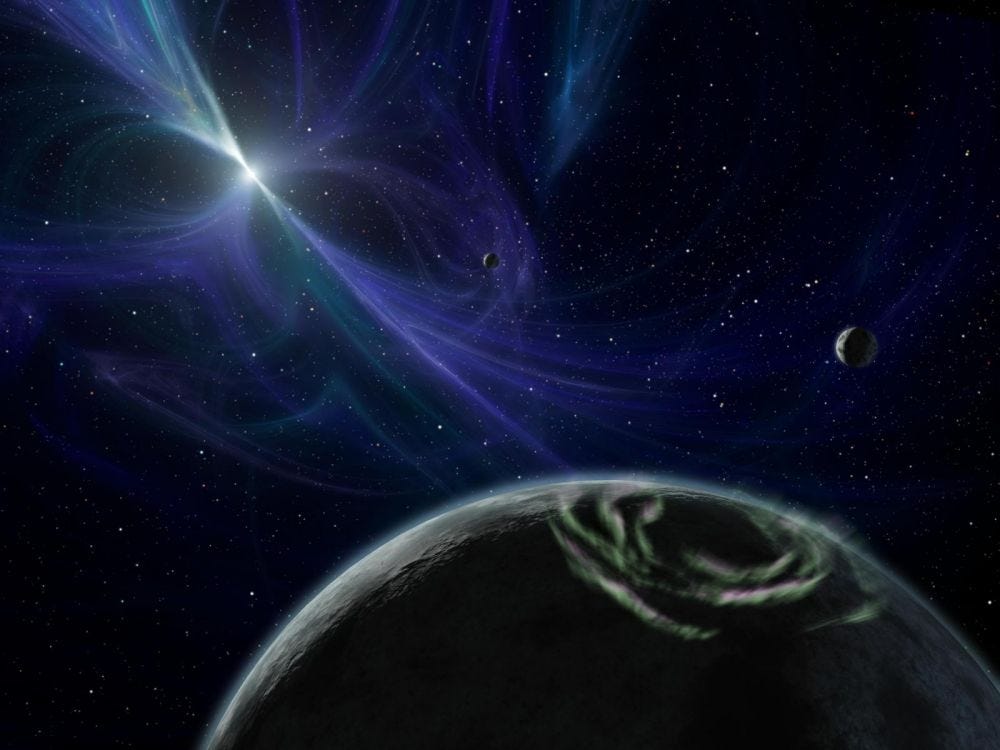

It must be said that the environment around pulsars is not conducive to the formation and survival of planets. Indeed, a pulsar is the remnant of a supernova condensed into a tiny neutron star. This object is extremely dense: the mass of a cube of one centimeter side filled with neutron matter is one billion tons! Particularly stable, the pulsar also rotates on itself (up to 1,000 revolutions per second), has intense magnetic fields and emits radio and X waves from its magnetic poles which seem to pulsate when the star rotates. How can planets form in such an energy surge? This is still a mystery to astrophysicists.

Despite the rarity of pulsars with planets, the Manchester team has nevertheless found about ten of them that could harbor planetary candidates. The most promising seems to be PSR J2007+3120 which could host at least two planets, with masses several times the Earth, and orbital periods of 1.9 and 3.6 years. Other data confirm that planets in these systems have highly elliptical orbits, which implies a formation process very different from the pattern studied for systems with a solar-type star.