Ultra-high energy cosmic rays: the noose is tightening around their still unidentified source

Paid subscribers

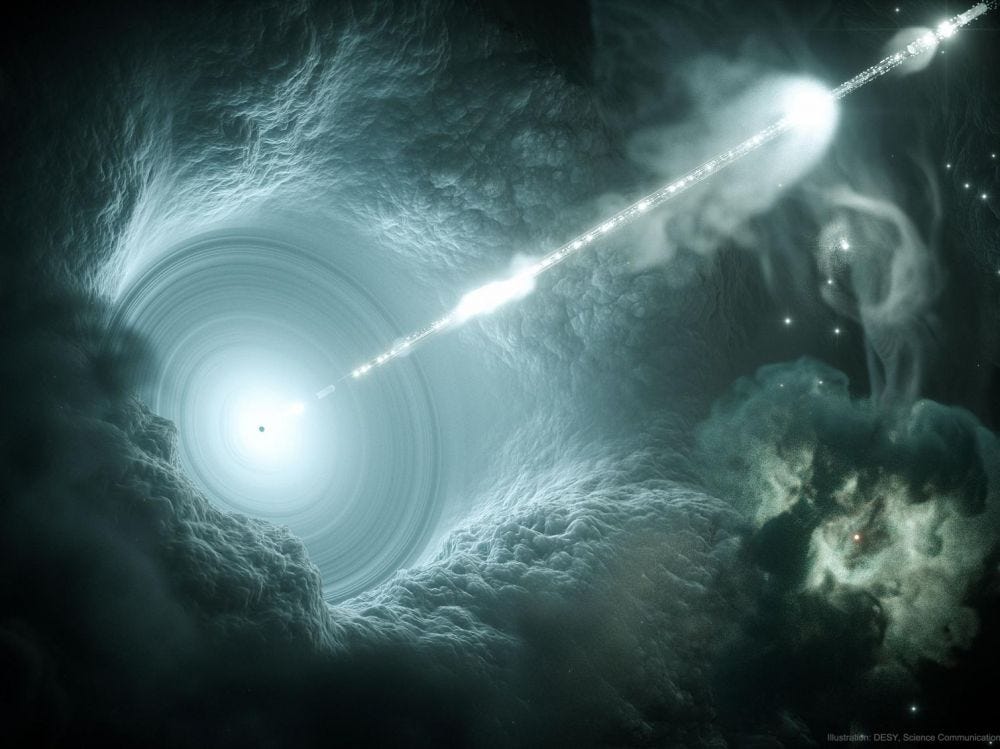

In 2017, the identification of a neutrino from a blazar, a supermassive black hole at the center of a very active galaxy, had marked a turning point in high-energy astrophysics. Today, the researchers behind this previous result confirm with new work that the active nuclei of galaxies are indeed natural particle gas pedals at the origin of neutrinos. This is a breakthrough in the understanding of high energy cosmic rays.

Cosmic rays, charged particles that travel at nearly the speed of light from deep space, constantly bombard the Earth. Since their very first observation in 1912 by the physicist Victor Franz Hess, made from a balloon, our knowledge of these extremely energetic particles has increased. We know, for example, that the vast majority of them are found in the form of hydrogen nuclei, the lightest and most common element in the atmosphere. But also, less frequently, in the form of helium nuclei and, even more rarely, nuclei of heavier elements such as uranium.

Energy monsters with an enigmatic origin

We also know that the energy of cosmic rays ranges from about 1 GeV - equivalent to the energy produced by a relatively small particle gas pedal - to 108 TeV, or a million times the energy generated by the beams of Cern's Large Hadron Collider (LHC), the most powerful gas pedal in the world. The source of the lower energy cosmic rays, also called primary cosmic rays, is more than familiar to us: they are produced by the Sun, and brought to Earth in the form of solar winds. Low energy cosmic rays are mainly associated with supernovas and gas bubbles. But the origin of the most powerful rays remains an enigma to this day.

These so-called ultra-high-energy cosmic rays raise a whole host of questions for astrophysicists: How do they reach such high energies? What could be the natural gas pedals that generate them? And above all, how can we trace them back to their source? Unfortunately, it is impossible to simply "retrace their route": made of charged particles, the turbulent magnetic fields of our galaxy have never ceased to deflect them during their journey to us.

However, a team of researchers led by Sara Buson of the Julius-Maximilians-Universität (JMU) Würzburg in Bavaria, Germany, has likely uncovered the most serious lead to date in this arduous hunt. The work of this group will be published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, already available on arXiv.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to NEWSLETTER " the Astro Journal " to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.